AMP Deputy Chief Economist Diana Mousina looks at the outlook for consumer spending and saving.

Australian consumers have faced many headwinds over the past 18 months, including high inflation – especially for essential items like groceries, electricity, gas and petrol which make it difficult to reduce spending – negative real wages growth and a large increase in mortgage repayments, due to the rise in interest rates since May 2022.

This challenging backdrop has resulted in some decline in consumer spending, with discretionary spending down by an annual 4% in the March 2023 quarter and retail spending negative over three consecutive quarters to June.

But spending has been supported by a high level of pent-up savings that has allowed households to cushion some of the recent negative hits.

So how much longer can Australian households draw down on their savings and what’s the outlook for consumer spending?

Consumer savings – the rise and fall

The savings rate – defined as the difference between household disposable income and consumer spending – has averaged 9.4% over the past 60 years (see the chart below).

Australia Household Savings Ratio

Source: Macrobond, AMP

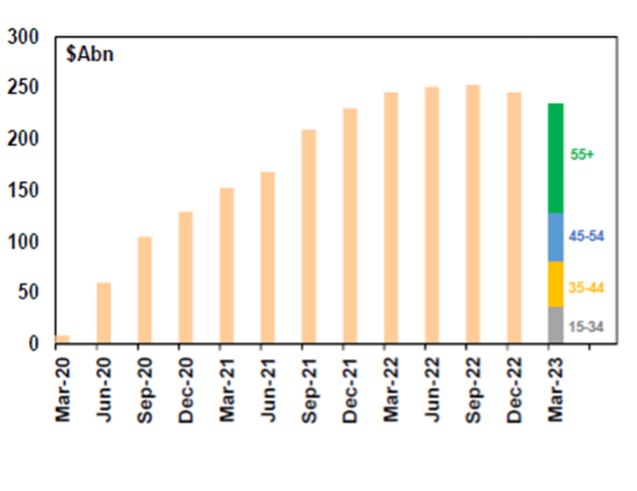

In 2020, the savings rate shot up as consumers got a boost from government stimulus packages. Meanwhile, spending declined as services were limited in lockdowns and high uncertainty made consumers more cautious. Consumer savings reached a high of $253 billion and 11% of annual GDP or 22% of annual consumer spending1.

Since this peak, consumers have drawn down just 7% of their savings (up to March 2023). This would imply consumers could still have another 2-3 years of savings to work through. But we expect the run-down of savings to pick up pace throughout the remainder of 2023 due to:

- delayed impact of rate rises

- roll-off of fixed-rate mortgages to variable rates 2-3 times higher

- impact of elevated inflation.

We expect accumulated extra savings to be mostly exhausted by late 2024.

As a comparison, American households are running down their savings faster than their Australian counterparts and we expect US savings will be exhausted by March 2024.

Winners and losers – Boomers vs Gen X

The headline figures mask divergence across different household groups, with saving and spending varying widely across Australia.

Older households (aged 55+) hold the highest share of savings (see the next chart) and bank deposits.

The argument around high household savings is that these will help consumers meet higher mortgage repayments and cost of living pressures which will keep consumer spending from falling significantly.

But older households tend to have smaller mortgages, so are less impacted by rising interest rates. And they may also be less inclined to spend their savings in retirement.

They would still be affected by the cost-of-living issues so excess savings would be useful in meeting spending requirements from price rises.

Middle-aged households (aged 35-54) are most impacted by rising interest rates as they hold a large share of mortgage debt. This group has little excess savings so will have to cut back spending.

Australia Accumulated Household Savings

Source: ABS, AMP

What this means for consumers

As household savings are run down, we expect the rate of consumer spending to start falling by late 2023 and into early 2024, which will weigh on GDP growth. While retail spending (33% of total consumer spending) has already started to decline, further weakness in broader consumer spending is likely as the cash rate remains high (with the risk of another rate rise) throughout the rest of 2023 and into early 2024, which will send household mortgage repayments as a share of income to a record high (see the next chart).

Australia Housing Mortgage repayments

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

The expected weakening in the labour market is also a risk for consumers. We see the unemployment rate rising from its current level of 3.5% to a peak of over 4.5% by mid-2024, which will put a strain on household spending.

On the other hand, consumer spending could receive a surprise boost if the labour market holds up better than we expect or real wages start to increase.

This article has been written by Diana Mousina, Deputy Chief Economist at AMP.

1 ABS,AMP

Current as at October 2023

Important note: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this document, neither National Mutual Funds Management Ltd (ABN 32 006 787 720, AFSL 234652) (NMFM), AMP Limited ABN 49 079 354 519 nor any other member of the AMP Group (AMP) makes any representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this document, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This document is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided. This document is not intended for distribution or use in any jurisdiction where it would be contrary to applicable laws, regulations or directives and does not constitute a recommendation, offer, solicitation or invitation to invest.